Winter in Ithaca: an essay on The Flaming Lips

by J.R.

I was living in Ithaca, NY when I was first introduced to The Flaming Lips. Ithaca has the privilege of steep hills, large, healthy trees, and imposing Gorges that gush with waterfalls. At the time nothing was more exciting than walking through this landscape with headphones on. Whatever is playing in your ears has a way of seeping into everything surrounding you—my heartbeat would grow heavy, and my legs would feel lighter than ever. In the dead cold of winter, The Flaming Lips’ triumphant songs resonated especially well. They are one of those bands who despite having gone through major transformations over their career always express—whether in their mid 80s grungy punk or their late 90s psycho-pop—the same enthusiasm, the same rebellion, the same philosophic longing.

At the time, to explain this phenomenon to myself, I concluded that Wayne Coyne, the songwriter and inspirator of The Flaming Lips, had a mystical connection with the world—and since I was young, and desirous of intensity and power, I wanted to become Wayne Coyne. I wanted to exist in his body, and every song gave me the opportunity to imagine what it would be like to do so. Soon this obsession started to terrify me, I would wake up, look out at the snow-filled window, and instead of perceiving what I perceived, I would add to the frame whatever it was I imagined Wayne Coyne would see when he looked out the window; and since many songs were about ‘spacemen and their guns’, ‘elephants and kangaroos’, ‘hypnotists’, ‘aliens’, and more, the possibilities seemed so limitless that I would always grow despondent after a few minutes, certain that the trapeze artist I had conjured was nowhere near as detailed as the full circus Wayne would surely have been capable of imagining.

I always had a notion that I was sick for having this obsession, that all my fears were only within me. Since I was corrupted by psychedelics, the odd guitar timbers and multi-layered melodies stole my mind off to an expansive oblivion. So I decided that this feeling of indeterminacy that came over me would only disappear if I became the creator of it. Wayne Coyne represented the limit of both a fear and a euphoria inside of me. He was the one who existed outside the infinite. What made this obsession even more difficult to shake was that while I was raising Wayne up to this holy distinction, Wayne himself, in his youth, constantly sang about Jesus, and I just assumed that he was referring to himself, especially when he sang, “Jesus was a rock star who destroyed all he’d seen.” It took me over three years to shed myself of Wayne Coyne, and when I finally realized I was out from under his spell, I was never entirely certain why he had left—it may have been that I replaced him with another vision of omnipotence, a friend, a lover… But I continued to listen to his music, because it always reminded me of a formative stage of my existence. Not to mention that those aspects of the music that had always appealed to me–the sense of humor, the honesty, and the absurdity–continued to suit my mood. So, it was not without a certain irony that, deep within Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, I turned back on some old tunes by the Flaming Lips only to discover anew what the songs meant to me back then, why they swallowed me whole, and why, still to this day, they represent that late adolescent struggle immortalized by Hamlet’s schizophrenic consciousness.

I have decided to lead you through my ‘juvenile hangups’ by discussing the first five songs on the album In a Priest Driven Ambulance Car, considered by many to be their first masterpiece. I should also explain the rarified Hegelian logic that I subscribe to these songs. One of the central themes in Hegel’s Phenomenology is the oscillation between the object and the subject. In certain instances of the “Spirit”, Hegel describes how our self-consciousness overemphasizes its subjectivity, that there is too much ego, and in other instances he observes the opposite, that the object is given too much value. I read the songs to follow along these lines, where each one overemphasizes or downplays the ego of the singer, Wayne’s ego. Like Hegel, who ends the Phenomenology with the perfect balance between ego (subject) and object, I will argue that the 5th and final song in this essay achieves such a balance.

The first song on this album is entitled Shine on Sweet Jesus on Me (Jesus Song #5):

Waitin’ for my ride

Jesus is floatin’ outside

(shine on, sweet jesus, on me)

Watchin’ the water rise

I’m gettin’ lost in the tide

(cry all your teardrops on me)

While I’m still myself,

Your blankets covered me

Covered me while I was still asleep

Watchin’ the planets shine

Reflecting yourself in the sky

(shine on, sweet jesus, on me)

Scraping these smiles of mine

Impossible one at a time

(cry all your teardrops on me)

While I’m still myself,

Your blankets covered me

Covered me while I was still asleep

Jesus is at my side,

Wondering what he will find

(shine on, sweet jesus, on me)

Watchin’ the water rise

I’m gettin’ lost in the tide

(cry all your teardrops on me)

While I’m still myself

Your blankets covered me

Covered me while I was still asleep

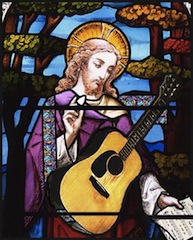

As a secular Jew, songs about Jesus remained a mystery that I assumed had some cultural significance, one which I was lucky enough to be exempt from. So what struck me back then was the way Jesus symbolized Wayne’s desire to toy with truth. The sight of Jesus “floatin’ outside’” somehow surpassed the surreal images on earlier albums, such as: “Brains falling out of my head.” To sing about Jesus instead of “monkeys humping holes in brains” transcends the vain and circular fight of the artist who thinks that extreme picture-thoughts provide the greatest impression. In singing about Jesus, Wayne externalizes his conception of himself and refuses to project his particular genius. So, to me, this song represents the refusal to make a great work of art. Jesus is floating outside not because a single consciousness has pictured him, Jesus is floating outside because the artist has sacrificed his personality and decided to bear witness to what is there when he is not there at all. This is why Wayne sings, “While I’m still myself/Your blankets covered me/Covered me while I was still asleep.” Often obsessed with describing the rancor of dreams, Wayne removes his ego completely from the process, eliminates all his dreams, and observes himself as a mere object in the care of a transcendent figure. Still, this figure is not exactly anonymous, it is someone who is much like Wayne himself (look at the picture of young Wayne), someone long-haired, whose exuberance, well, this is how I saw him, could forgive all sin.

Wayne’s ego returns in this unavoidable identification, but does so in the form of a living God who is immune to the vanity of dreams. You only need to listen to these songs, recognize the playful marching beats and the wistful nature of Wayne’s crooning, to convince yourself that these songs are indeed a joyful act of self-annihilation. This is why Wayne does not maintain a common theism throughout the whole album or even the song itself. He possesses as many ways to abandon himself as the boundless picture-thoughts he now sacrifices.

The first line of the second verse “Watchin’ the planets shine/reflecting yourself in the sky”—is not inspired by any Christian notion that I know of, and this complicates Wayne’s gesture, since he is not grasping for a stagnant mediator of objectivity but for the process of objectification itself—so that the vastness of the Universe, either in its scientific module or in the module of ancient heroes and gods, now replaces Jesus, but recreates for Wayne the objectivity necessary to reflect not into his ego—but out of it.

***

When I was obsessed with the Flaming Lips, I was also obsessed with hallucinogens, most specifically mushrooms, but I did a good amount of acid as well. I had a friend who was attending Cornell for free because of his peculiar genius and instead of working to assure safe passage through the world, he became the biggest drug dealer on campus. Psychedelics tend to promote communities in which everyone seeks to project themselves as nearest to the heart of a great mystery. “Knowing” in its most naked element was what we all desired, and my friend Darian seemed to be at the top of this Caste system, handing out pieces of advice for cash. He also managed to ace his chemical engineering classes while staying up all night preaching the messages whispered to him in the nearby forest. Being with him, doing acid, and listening to The Flaming Lips—all these things interwove to spur on my personal reinvention—and I took all these things much more seriously than my literature classes.

In Hegelian terms, my classes were all limited to reflective thinking, to boundaries, to limits, to qualifications of what knowledge was supposed to mean, whereas, at night, by the waterfalls, in the infinite melodies, speculative thinking tore away all stationary manifestations of existence. I was religiously attune to these methods.

Unconsciously Screamin’:

Seeing the unseeable,

Filling down the void

We’re not what we used to be

We’re not really boys

Screaming till our lungs are full

Kicking down the teeth

We’re not what we used to be

We’re just paranoid

Unconsciously screaming

And whispering at everything she brings

This song is violent. It begins with loud hits on the snare, strong distorted guitars, and Wayne’s shouting voice. The band is laboring in search for knowledge—they do so by negating all objects of perception. Sight is unseeable, the human is no longer human, no longer a child, and teeth are breaking. And what else is all this but paranoia—but then all this breaking down is negated too. So that the void, instead of causing vertigo, fills up with this non-sight, the void solidifies. Unconsciousness destroys the volition of the punk rocker raging against the machine, it turns his cries into a mere whisper. This unconscious whisper is then identified with She, with nature, with Mother Mary, who “brings” despite the repetition of unsight and the damaged ego of drug-addled youth. What in the first song appeared in a vision arrives in this song as the process of lost vision. The identifying object is not the Lord but the vicious circle—a movement one must continually exert.

“We do it wrong, being so majestical, To offer it the show of violence, For it is as the air, invulnerable, And our vain blows malicious mockery.”

My favorite line in this song was always “We’re not what we used to be/We’re not really boys.” Fearfulness and liberty alike inform this transformed idea of identity. It is both a reflection on maturation into adulthood and on how the human grows out of its categories. There is not a period of one’s life that is more prescient of what will become the constant dissatisfaction of self-identity than the one that forces the boy to reinterpret himself outside of his parental instructions. This is the limbo where one MUST, if one is to approach liberation, ask the timeless question in Hamlet. It is also the limbo where one must accept that Being will never be forthcoming with an answer. The Flaming Lips transgress this limbo—they proudly assert the negation of all categories—they are growing out of their youth, and yet maintaining it with the rebellion of infinite resignation, letting IT take them wherever their violence and non-sight brings them. And this leads them back into themselves.

Rainin’ Babies:

What I’m thinkin’ is so delicate

If I breathe, you know, I’m gonna lose it

It’s just a drop in the biggest ocean I know I’ve ever seen

And in a moment it’s big enough to drown the whole world

This is my present to the world

And I want you to take it

This is my present to the world

Take it from me, please please take it from me

All I know is I don’t know it

It’s rainin’ babies from the sky down on me

Tiny drops on my windshield

And in a second it’s rainin’ rainin’ all over the whole world

I used to think that Wayne was such an arrogant, fucking asshole for singing this song, for regarding himself in these messianic terms. Now I see how reaching unflinchingly for the messianic immediately overcomes the very psychic limitation that made me so angry that these words were spoken by someone else, who was not me. In other words, these lyrics forced me to face my own desire and failure to be messianic. In the ever-changing confrontation with what is alien in the self we find a way to refuse our own vanity at the exact moment when this vanity expresses itself.

If we think chronologically about the psyche of the artist within the structure of these particular songs, the urge for the surreal, for the shocking, constitutes the first moment (the moment before the most successful expressions in this album)—in such cases,value is given to an external marker (that of pyrotechnic mental capabilities), so that the contradictions inherent to the act of expression are not accounted for in the work itself. Next we found that the artist replaces the pyrotechnic image with Jesus, but at the very moment Jesus triumphs over all picture-thoughts, he becomes one himself, and so we return to the unconscious screaming, that place where nothing yet has been proffered.

With the internalization of the offering, the song above speaks solely to the skeletal structure of singing, of art. That which is desired will be destroyed if one single breath is taken, if one word is uttered. This word is singular, it is one drop, and yet, in that it “arrives”, it becomes universal, it swallows the whole world, and it is this paradoxical breathtaking moment that is Wayne’s present to the world.

“Please please take it from me…” is an elemental prayer, one which prays for language to continue mediating. This notion of presence, the one that will be destroyed in becoming Word, is no longer the great weight that burdens the artist. It CAN be transmitted, but what do we transmit if nothing is ever spoken? The gift offered by the artist is in reality a plea by the artist to maintain possession of himself without fearing that in not speaking he sacrifices all transmissions… the gift given is the realization of the paradox of subject and object, the singer refuses to identify with a concrete image or even a word. Encircling the dialectic in this way, Wayne can in fact be heard praying to himself, “This is my message to the world…take it from me, please please, take it from me.” He can be heard voicing the plea of the universal, take me into you, this is my message, just this, my plea.

I was not able to possess this gift immediately. I heard Wayne cajoling me to believe in him. Looking back, I don’t know what I could have thought I was supposed to believe in. While Wayne sings of sacrifice, I refuse to do the same—I project (give, present) him with my own self-consciousness, one which still believes that my utterances have particular relation to myself…Wayne is broken apart, refusing to give anything, and all I could hear back then was my own particularity were I to sing such a song and tell everyone how great I was because I had a present. I was unable to realize the irony of that which was present.

***

My friend Darian and I rarely talked about the Flaming Lips, mainly because Darian was always talking about himself, and his music taste was different than mine—he liked punk music and The Grateful Dead. Whenever he spoke madly and convinced me that he was omnipotent, it was always a nice consolation to know how bad his taste in music was. I remember one night he started to obsess over his connection with Hamlet—this was like a challenge everyone in my school seemed to take up at one point or another. And though Darian was illiterate, and had only the Celestine Prophecy on his bookshelf, he too found his way onto the ego trip the Prince of Denmark symbolizes. On one of those cold nights of which there must have been over a hundred each winter, Darian and I ended up taking two chairs into the co-ed bathroom shower stall and turning all four faucets on to the highest heat so we could smoke a joint in a makeshift steam room. While we were in there, Darian stood up and began illustrating to me the way his energy takes him by the reins and whips him about in every direction. It was then that he compared himself to Hamlet. He had no control over himself, he said. He feared that he was going to kill someone one day, and he made a point of asking me how I deal with all the pain and rage, and I just said that I must not feel as much as him, that things must be easier for me, and he consoled me for having submitted myself as such, saying I was a really good friend. But at that moment I had conquered him, I had experienced his ego and refused it; instead of projecting my own suffering, I remained silent.

Take Me Ta Mars:

Yeah, ’cause when I drive in my car

We put heads into jars

So take me please, take me to mars

I wanna go where they are [2x]

I wanna go

Yeah, and if I’m lost, well I don’t care

’cause I walk on endless stairs

You say it’s me, I think it’s you

Who can blame us for thinkin’ the way we do

’cause we don’t care what we are [2x]

Take me please, take me to mars [3x]

Take me to mars [5x]

I would say that this song is not as brave as the other songs, this is a song about ego-tripping off of alienation. It is about returning the gratuitous violence of existence with one’s own gratuitous violence. But I always loved this song the most exactly because it asked for the least amount of sacrifice; as such, I could remain within myself while feeling utterly different. This was the kind of song that inspired me to imagine all sorts of bloody disfigurations of the people I was passing by. Everyone was guilty of not being different like me, and so to maintain this satisfaction, I had to rid the world of everyone but myself. This then brought me to a barren world, bloodied red, but I didn’t care—and who could blame me for thinking the way I do. As Wayne once sang on an earlier album: “If you don’t like it, go write your own song.”

***

I did in fact believe I was the messiah for a few hours one evening. Darian brought over these spidermen acid tabs and while we were waiting for the drug to kick in, and while Darian fussed about with the stove, I desperately needed to be alone. It was only a week after September 11th, so there must have been a lot of gravity in the air. When I made it down to what we called the “meditation bridge” the yet to be frozen-over water roared so immensely, and the stars above were crystalline. It was a very metaphysical experience. I drew out my plans for salvation across the cosmos. Darian seemed somehow an asset to me in this frame of mind, somehow it was up to me to harness his power in the correct geometric shape. I don’t exactly know how to describe what I felt then, I guess it was just an extreme rush, a full-frontal confidence. I was the falling water and I was also whole, specifically me. When the drug finally wore down I felt a tremendous and rather relieving collapse back into myself.

Five Stop Mother Superior Rain:

I was born the day they shot JFK

The way you look at me sucks me down the sidewalk

Somebody please tell this machine I’m not a machine

My hands are in the air

And that’s where they always are

You’re fucked if you do, and you’re fucked if you don’t

Five stop mother superior rain

I was born the day they shot john lennon’s brain

And all my smiles are gettin’ in the hate generation’s way

Tell ’em I’m gonna go out, shoot somebody in the mouth

First thing tomorrow

[chorus]

I was born the day they shot a hole in the jesus egg

Now the rain, it’s all so random

What does free will have to do with it at all?

And you can’t cry, but

It really don’t matter, y’end up cryin’ anyway.

[chorus]

I believe that this song incorporates all the variants of subject and object from the four prior songs into a metempsychotic journey that, though abandoning the self, remains transparently grounded in such a way that the specific human comes forth in all his love and hatred. No matter where the self originates, no matter where it transmigrates or disappears, it always returns to originate, disappear, or transmigrate. All its nascent forms are historical figures (John Lennon, Jesus, JFK) who represent hope and possibility, each of whom was killed for their revolutionary message. But the message, the same one that remains unspoken in Rainin’ Babies, returns in the disaster of self that loses itself only to arise anew. Now, at last, with the internalization of the external presence of the self, Wayne has self-consciously raised his hands in the air in a gesture of hope and hopelessness… pleading, praying and embracing that which inhibits him from crying, and then makes him cry all the same. Five Stop Mother Superior Rain, who I imagine as the same figure referred to in Unconsciously Screamin’, is neither outside of each figure nor inside. Wayne’s hands are in the air not in prayer to this Rhea or Mother Mary like figure; no, the hands are SHE…whose Reign is all so random that the ultimate freedom is only achieved in the question of free will itself.

This song attains an overemphasized utterance that pulls the slates out from under every ground, so that the movement itself becomes the only mode of beginning and end. And in what is a triumphant call to arms to the musical generation singing all around Wayne and the Flaming Lips—this song calls attention to the impossibility of refusing the smile, the one which decimates the skepticism of the punk rockers, and thusly explains why Wayne later re-titled this album: Finally the Punk Rockers are Taking Acid.

***

My friend Darian ended up trying to kill himself. He had me chase him for five hours in the middle of the night, threatening to use the butcher knife he stole from the mess hall’s kitchen. He had a letter for me that I was supposed to send to his parents—but I ended up calling them right away and they drove up from Pennsylvania and took him out of school for a few days. He never did anything, and when he returned he was exposed, and he knew it. Unable to realize the limitless in his own life, he bound himself to the image of suicide as that which would prove his ego limitless—but, unable to accomplish this action, he had to face his own limitations. And he was humiliated as a result. For me, whatever glory I once attributed to his psyche was also demolished. He had been posturing all along. He had always wanted to be that ‘no longer boy’ who walks on mars, and this resulted in a denial of the ground actually beneath his feet.

***

I guess all of these ideas help me understand Hamlet’s indecisiveness. Hegel seems so useful because, even without fully grasping his language, he always exposes the various ways a self-consciousness, an ego, can remain stuck in a flawed identity. I remember my teacher at the time, who was old and hunched over and uninspiring, made a big point of explaining that the ghost of the father was a real figure on the stage—you couldn’t diagnose Hamlet with madness without implicating yourself in his affliction. If Wayne Coyne and the Flaming Lips have, in their own quirky way, successfully mastered the process of self-alienation, Hamlet is a complete failure—his failure is caused because he can never rid himself of the real objective existence of that which terrifies him. Whereas that which haunts the singer in Wayne’s songs is always unmentioned or impossible to grasp, Hamlet is confronted by a real crime and a real ghost. As a result, he is unable to dislocate from his particular mother and particular father—this creates for him his alarming self-consumption. It is as if the mother and father figures in his life so fully embody the universal metaphor of self and object that he is imprisoned on the dead end street of teenage angst. Hamlet reveals his fixation when he wonders about the dreams that come after death. These dreams, he worries, still might come to the particular, tarnished, battered self… It is of course those who cannot ‘break down the molecules’ of selfhood in their own self-consciousness while still alive that have the bravado to wonder about the possibility of eternal torment. The eternal IS already, in the figure of the waving hands, and in the rebirth of souls—a self taken into and out of itself in a persistent dispossession of both full selfhood and pure selflessness. Hamlet’s indecisiveness occurs because he confines the philosophy of the world to his small little stage—he can find no recourse to shirk his desire to be a self. The resurrection of the father is not the image of the external Jesus but a vain reflection of familial insularity. Hamlet is one of those brats who continually reminds his friends that his family fucked him up…

I don’t remember if I ever contemplated suicide. I know that I would lie in bed and imagine axes splitting off my head, but this just felt like therapy. Many times I would take my headphones down to the Gorge and listen there for hours, screaming along to the lyrics, and this was helpful, I think, much more than trying to make believe I was some tragic hero.

God Walks Among Us Now:

How does it feel to be breakin’ apart

Breakin’ down molecules

How does it feel to be out of control

Another ring around this ball

Used to be all right

But things got strange

How does it feel to be fallin’ apart

Sinkin’ from the bottom down

It’s not so easy holdin’ it up

With everything fallin’ down

Used to be all right

But things got strange

Used to take all night

But things’ve changed and God walks among us now

“O that this too too sullied flesh would melt, Thaw and resolve itself into dew, Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d his canon ‘gainst self-slaughter. O God! God!”